2/04/2020

You make my neck ache.

You make my arms ache.

You make my back ache.

You make my legs ache.

You make, surprisingly, the arches of my feet ache.

You make aching into a form.

You make aching hold volume.

You make aching move.

You make aching cast a shadow.

You make aching a thing unto itself.

You make aching addicting.

You make aching pleasing.

You make aching worrying.

You make aching gratifying.

You make aching in a way, I’ve never before ached.

You make me want to suffocate.

You did this.

You make.

3/04/2020

I must apologise for yesterday. It is clear to me now, after a good night’s sleep, that I was rather agitated. Riled up, as it were. And to tell you the truth, I was a little bit nervous. So, as a result, I took my frustration out on you. Which I am ashamed of. Truly. I don’t expect it to happen again. But, if it does, you must promise to speak plainly, and clearly, as I won’t tolerate your dissatisfaction—I don’t want us to drift apart.

Apart, I sigh, before we have even begun.

To begin is often thought to be the hardest part. Part of what, you may ask yourself. Well, part of the whole. And what is the whole? The whole is something which, I must admit, I am still navigating; however, I expect the whole would have a start and an end. But again, what defines the start, and what defines the end. Do you? Do I? Do we? Who shall we turn to for an answer? For a line, clearly drawn in the sand. You, no, you; yes, yes you; line-up, toes on the line, back straight, shoulders back, breathe, I said breathe; on your mark, get set, go!

You bolt from the line.

Or does the line bolt from you?

This part then, is something difficult to define. And whose to stay it goes in a straight line, like our runner, hurtling along the sand. As it happens, this whole I imagine, is not straight, but round, like a circle, or a slice of pie. It actually reminds me of a diagram, of those tedious fractions which we learnt at school. Those fractions, were often three-dimensional, much like our pie. They had depth; their section, their part, travelled up, down and through the whole. And this depth is something all together unpredictable too—depth grows depth, you see.

I sense I have confused the matter.

I need to stop this frantic energy.

Perhaps it’s hard to begin, as beginning means roughly understanding what this thing is a part of: what piece, what fraction, does the beginning mean, to its whole? Anyway, you don’t have to answer that right away. Muse on it. Absorb it. Drink it all in. We have the time—some would say, all the time in the world. And just as the runner returns, to find their line again, we may realise that this beginning has been swept away, by an incoming tide.

I guess it’s up to me, to draw the line again.

4/04/2020

Isn’t apart a rather odd thing.

I mean, just look at the word itself.

To be apart, means to be s-e-p-e-r-a-t-e.

But the word itself remains together.

Whereas, to be a part, is to be together: a part of something. But the term itself remains s-e-p-e-r-a-t-e.

Weird, huh?

5/04/2020

You may be wondering as to why you’re here.

And sometimes, I wonder the same thing myself.

Although, you’re not quite here, are you?

I keep forgetting that. There’s here and there’s there.

It might then be best to say, you are approaching here.

To reaffirm our position: you approach here, from over there.

6/04/2020

You know me as I know myself.

Or maybe, even closer than that.

And that puts me off balance.

7/04/2020

I want to know if you’ll stay there.

Firmly rooted in the ground, so to speak.

As I make my way through this forest, will you stay still?

I’m worried, that if I get to somewhere, I won’t know where to go from there.

Somehow, instead of you approaching me, I find myself reaching for you.

I stretch my arm out, open my hand, and wave it, as if feeling for a wall in darkness. An act of will, but exactly whose will, again, I’m not entirely certain.

I feel an immense pressure rise within me.

My mouth is dry, my knees, weak.

I’m not sure what you meant.

8/04/2020

I wonder to myself, whether I should leave you loiter.

Loitering outside, in the rain.

I’m struggling with it.

With this decision I must make.

I do not suggest that I find your demeanour distressing, or even menacing, as if you startle me, by skulking around outside. I am not unsettled by your face, or at least, I don’t believe so. I’m undecided. I have not yet materialised the face of you. And to do so would be wrong, I think. It exists like a crying window, full of distortion and glare. It’s hard for me to explain.

We are close, but far.

I can hear you mumble and murmur.

The thing is, once I let you in—you’re in. There’s no pushing you, our guest, back out into the rain. It’s a one-way ticket. Into this warm, cosy room, I call myself. But this self, at the present moment, is not quite itself, and you may wish to turn on your heels, and go in search of someone else. I give you this warning: go somewhere else. There’s a chill in here too, the fire is struggling, its embers, lessening. Growing cold. I fear to be stamped out.

You seem to be quite enjoying the rain, dripping down your face. You don’t seem too cold either, or discontent.

I shall leave you loiter.

A while longer.

Apart.

9/04/2020

You breathe, heavy, on the window pane.

My sight obscured by your breath.

10/04/2020

You’re tapping, tapping, tapping on the glass.

Incessantly tapping.

11/04/2020

The wind picks up.

A breeze becomes storm.

12/04/2020

I can no longer keep you at bay, my arms unfurl, and I bring you into my embrace. You’re wet and cold; I rub your arms, vigorously, igniting your blood, into a dance around your body. Warmth fills your cheeks.

It’s time, I tell you.

Time to tell you.

I’m nervous, and I’m uncertain as to why.

Maybe I seek your approval, your acceptance.

Anyway, dig deep, I urge myself.

I must dig deep.

I’m determined to navigate somewhere; this task you set for me.

This arduous voyage across time and chance.

I… I… I decided to plant.

I planted a field.

I say so, with a tremor to my word.

With a crackle and a quake.

I planted it, in order to reach you.

13/04/2020

As much as words mean many things.

It is your nature to be many things.

By telling you, I risk changing you.

For the most part.

You are to be an image.

14/04/2020

I also planned to not only plant.

But to write to reach you.

To write to you.

I’m sorry, I can’t share any more.

I feel we’ve gone too far.

The more I say, the more I define.

And it’s important that you’re not defined by me.

I’ve been told I’m controlling.

And I know I mustn’t control you.

15/04/2020

The seer, sees and in doing so, is seen.

If only seen within himself.

16/04/2020

And so my plan is revealed. My intention, laid bare, albeit, only to a certain extent; we still have far to go together; many miles and many pages to cover. Up until now, I hope you haven’t found them too convoluted, my stories and tales I mean. I wasn’t aware of how ambiguous you wished it; how subtle, how direct, how within itself you wanted it. I think as we negotiate what it is, we shall fluctuate from within to outside ourselves. Oscillating between the two. Like air, drawn into my lungs, and blown back out.

I am relieved to start discussing what planting meant to me.

You see, we had chosen the field months prior; selecting it, out of numerous others. It had to be right. It had to feel right. And so we debated, and eventually whittled them down, like you would a block of wood, to find the perfect shape. We settled on our preferred choice and waited. Then, after a couple weeks flew by, we attempted to commence the process: to start planting the field. But, for some reason, you felt it not right, and sent the weather to hold us off; the rain poured, and poured, and the sun didn’t shine; I waited two weeks but you never let up. The soil was waterlogged. I was downcast, irritated and impatient. My concern was this: if not now, then when? I felt you were attempting to elude me, as if I was a stranger, following you down a dark, sinister street at night. And so you made me wait, and I waited and wondered, each and every day.

After six weeks, you changed your mood. The weather lifted and we began to commence for a second time. I was dubious, to say the least, unkeen to set myself up for another fall. But the day came, I arrived, parked, and walked into the field. The sun was bright, the sky was blue, and the earth, the earth was moist—it was just right. The field was unkempt; the grass, luscious, and a vivid green. The stage was set, so to speak, and we began.

First, I watched as my dad, cut the grass. He started from the edge, and made his way up and down the field, slashing at the lengths. Very quickly, variations of shade, colour and tone appeared in the field, along the lengths of grass already cut. They contrasted with each other, depending on the direction of the cut and your position. I walked up the side of the bank, and observed as the final strip was sliced, clean off; separating the image I knew, from its former, unkempt self, to a newer, fresher face. Appearances shifted, like quicksand.

The process did not stop there: next came a breaking, as the rotavator swept the ground, removing what little carpet of green was left. Uprooted entirely, and giving way to a light brown, dry soil, I felt as if we were grinding pigment in a pestle and mortar. The canvas too, was being stretched and defined, its dimensions becoming clear. I’ll forgive you for thinking that the boundaries of this task were a comforting sight. It is true, knowing the distance you must travel, does indeed help support your confidence in the journey. But here, here the distance was to the horizon, and I could not see to the other side. My body was confronted, with the scale of it, with its own minuscule nature against the expansive, devouring space of the field. I stood face-to-face with it, trembling.

17/04/2020

The following day, I returned to the field.

Today we were to plough.

The ploughman arrived. I observed a great, curved, metallic toothed monster, following behind him. I spoke to him briefly, before he set off. He seemed confident he’d make short work of it. The plough dug into the ground, penetrated it, and dragged. The tractor at first jolted, digging in, pulled back slightly by the unrelenting grip of the soil, it was hard, solid, iron-willed too. But alas, it gave itself up, and the ploughman started his way up the field, carving the soil. Turning it over, and over, and over. I could recall the soil very well, how dark it was and the smell of it—as if it had never before been opened up. The scent was like a forest of trees, ground up, layered and squeezed together. It was like time itself had released an aroma. Watching soil, deep, nutrient rich soil, being summoned from the ground, was like seeing waves appear, when the ocean was nowhere near. It gives you a sense of something essential, or fundamental, when you’re near it, as if the balance of the universe relies on it.

Tumbling, tumbling, tumbling.

The plough, in its wake, formed a landscape within a landscape. A thousand landscapes. The slopes and jagged edges shimmered. Angle, surface, texture, size, scale, depth, width, height and length, all paraded in front of me. I felt a sense of vertigo from the infinite. Perspectives bred like rabbits in the hedgerows. And it was then, I formed the realisation of what the world is made of: earth. I saw what God must have, when forming tectonic plates, and compressing them together, to force a surge, an uplift, of boundless energy. An endless mountain range appeared before me. And I fell before it, onto my knees. It multiplied inside of me and I inside it.

Crumbling, crumbling, crumbling.

As the ploughman progressed on, field turned into battlefield. The enemy approached from the western flank. I arrived in fallen worlds, only to stagger, clumsily, into another. My feet were alien to me. I pressed on. The sun in my eyes, sweat at my brow and a pounding in my chest. I felt a kind of catharsis in seeing something ravaged other than myself. These craters, these edges, extended out of me. And to move through them, was as if to come to terms with them, to map them, inside myself. Art is like the traces of wounds ploughed into the field. Ploughing reveals more than it hides. It digs up the root of things. It mixes in, parts of me, reached by light, and those untouched by it. The field eats itself. To produce from itself. You fuel yourself in ways unknown to yourself.

I waved goodbye to the ploughman, as he left, for another field.

A job well done.

18/04/2020

The field was being realised, ever so quickly, in front of my eyes.

Once I triggered the start, every stage seemed to be upon me.

The fertiliser rained down, like hail stones. Little white pellets of sustenance and energy, scattered: left, right, up, down. They filled the air and settled on the soil. Slipping into every crack and crevice produced by the plough. I thought it would take as long as the other work, but then the driver, promptly positioned himself in the middle of the field, fired up the machine, and commenced; within two minutes, the work was done. I was surprised at the speed of it, at the efficiency of the process. I merely blinked and he was gone.

We called for the power harrow, and soon enough, within an hour or so, it came billowing up the lane. I thought this machine similar to the rotavator, but it was heavier, stronger, with far more brute force. It started, like the others, by travelling up and down, moving right to left. It sounded like a high pitched wail, escalating, as the circular drum with blades spun, gaining increased velocity. A pummelling. A battering. It crushed and compounded. Ushering in, wherever it went, a uniformity. It levelled the earth. My sea of mountains became a mill pond, gently undulating. Behind the machine, from the right angle, you could see these cliff like edges being funnelled in. After, I was left with a smooth layer of finely prepared soil. I ran my fingers through it.

As we were pressed for time, they sent the crawler out too, whilst the rotavator was still completing the remaining half of the field. The crawler is a funny, little, yellow, aged machine. I remember it from when I was a boy. Over the years its parts have been removed, adjusted, fixed or replaced entirely. So much so, I wasn’t completely sure if I was looking at the same machine, or a patchwork, made of metal. And as its name suggests, it is a thing that crawls, on caterpillar tracks, thereby moving at a slower pace than most. It gave me a sense of something prehistoric, unleashed from a cage, as it groaned its way up the field. The crawler is tasked with directing the soil, balancing the flow, to create perfectly proportioned rows, or furrows, as they are known in the trade. These span the length of the field in parallel lines. These too induce vertigo, from a ceaseless progression, of up and down.

To observe both machines move around each other, on the same stage, was like watching a carefully choreographed dance, between two people. They sped up, they slowed down, they moved over, around and across each other. Each added to the other’s work, to the other’s movement. They pushed forward, together, and before long, the field was done, prepared, ready for another’s entrance.

For the final act, they brought a tractor and a trailer, carrying boxes of seed for me to plant. Thankfully, they placed these boxes along the furrows, at intervals twenty meters apart, to help my progression, along the field. I thanked them and they departed. They seemed to laugh between themselves, again, in disbelief. I was at last alone with no more distractions and no more observations. The task now fell to me, onto my shoulders.

19/04/2020

I am tempted to continue, to continue speaking like I have, over the past few days. But I think describing how I did this, or how I did that, may get slightly tiresome, for both you, to read, and I, to write. I also feel we’ve reached a point in this narrative, a juncture, where an attempt to convey, or interpret the nature of my planting, in its entirety, would be futile. I’ve learnt there are a few things beyond the reach of language, and this, in fact, might be one of them. Furthermore, somethings, after all, must be kept for myself. And so, rather than trying to climb a slippery, muddy slope, I shall merely stand at the bottom, and observe one or two things which crossed my path.

20/04/2020

My first observation, was actually a sensation, or to be exact, the lack of sensation. I had spent my first day in the field planting by hand. And as promised, I shall not bore you with the details. But you should know, I had committed myself, in body and mind, to the task at hand. I was planting as directed, up and down the furrows. The phrase back-breaking is often bandied about nowadays, but truly, I speak from a place of experience, it was indeed, back-breaking. I continued on, completed twelve rows, and headed home. I was exhausted. Spent. For the remainder of the evening, I was incapable of moving; my muscles ached, throbbed, burned, and at times were agonising and tender. I positioned myself in bed, moaned as I lay my body flat, and attempted to go to sleep. I felt my blood rush around my body and heat radiated out from me.

As I lay there, willing myself to sleep, dreading the following day, I noticed I could feel the weight of my body, more than ever before. The body declares itself subject! It made itself known to me, as an object, one with its own limits, boundaries and intentions. It had been thrown, you could say, by me, the pilot, into a nosedive, hurtling towards the ocean. It was alarmed, and alert. I realised then, it’s not normally one for my attention. I guess, I use it, without really considering it. When I was there, contemplating this new found knowing of myself, I located a place I could not feel, it was numb, and cold to touch. My left hand—to be precise, the right side, of my left palm—did not ache; truth be told, it did not feel anything at all. I squeezed and massaged it with the fingers from my other hand. It was lifeless. I had a strange sense of doubleness wash over me, of slippage: that feeling which occurs when your brain stumbles, trips over itself, unable to discern what it thinks it knows, from what it feels.

I ascertained that there, here, that padded piece of flesh, was where my weight rested, when traversing the field. I learnt that, to plant properly, you must hold the box with either your left or right hand; and instead of carrying the full weight of the box, constantly, you must channel your weight; support it, when bent down, through your hand, arm and shoulder; by doing so, you help support your back. Once your back goes, you go.

The human hand is commonly known as a grasping organ; it is so familiar, and so essential, we often overlook its importance. Its meaning can range across a variety of subjects too: in the hands of, implies the holding of power, wealth and authority; a helping hand, suggests the giving of assistance, aid and support; a big hand, often leads to applause, praise and adoration; to hand off, is to offload, or relinquish responsibility; show your hand, leads to the revealing of not only cards, but intent; by my hand, is literally, made by my hand (handwriting); a hand, is four inches, and a unit for measuring the height of a horse; may I ask for your hand in, is of course, marriage; and finally, although I’m sure there are many more, a hand, is a sailor in a ship’s crew, and by association, a labourer. This odyssey of meaning brought me to the word manual, which comes from the latin manus, meaning hand; and so, we arrive at manual labour, and everything, by extension, that uses a hand and the body.

As those thoughts whirled around my mind, I began to drift. You know, often, before having the courage to go toward the greatness of sleep, I pretend that someone is holding my hand and I go, go toward the enormous absence of form that is sleep. And when even then I can’t find the courage, then I dream. In your hands, you carry me.

21/04/2020

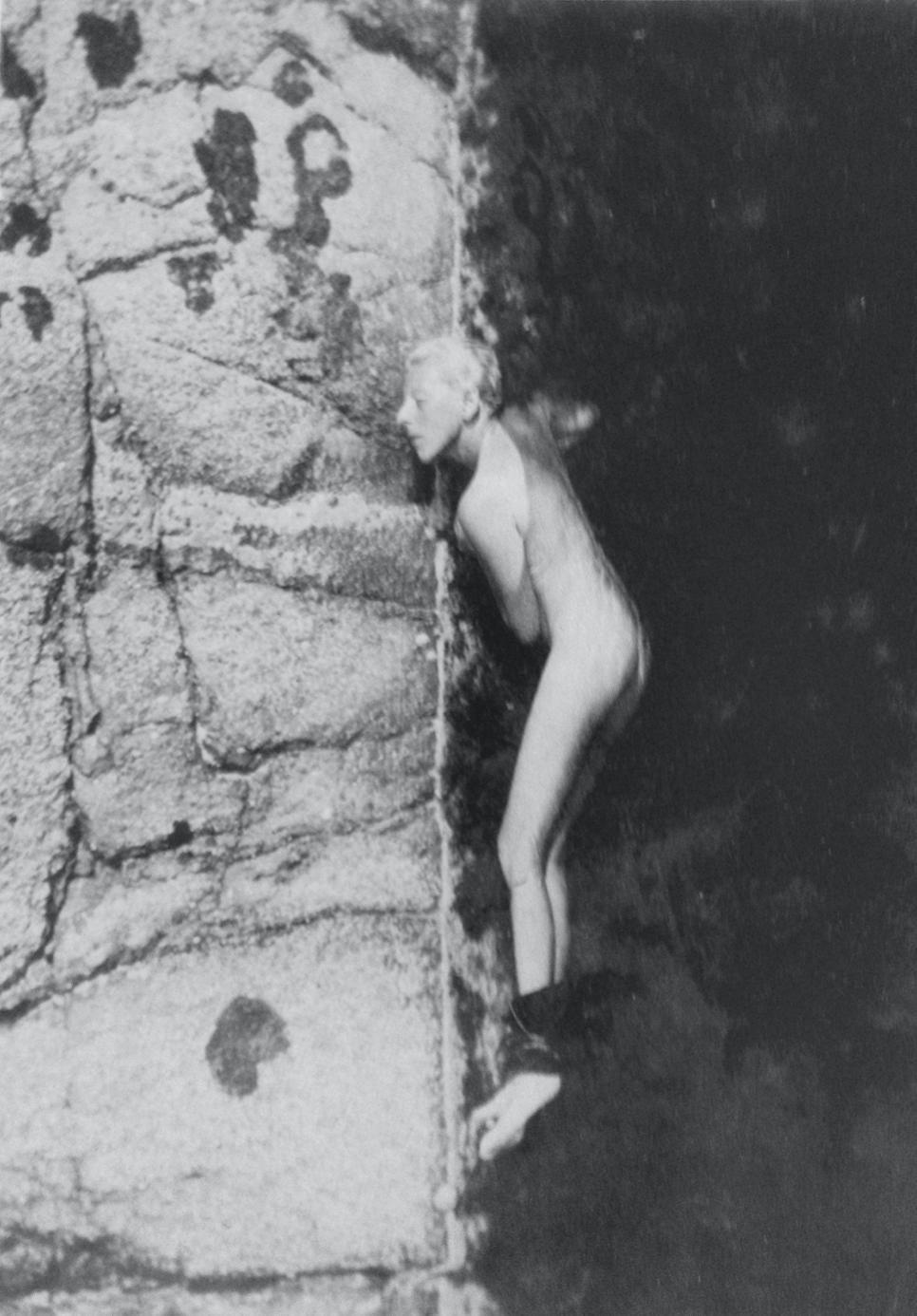

My second observation, was that of rhythm. It’s an interesting question, isn’t it: how to move? A few weeks ago, I found I had to learn how to travel over the earth, in a way unfamiliar to myself, but not too dissimilar to a rock climber, ascending a cliff face: grappling with the surface, weight forward, constantly in motion, building momentum and crucially, never looking back. I was, of course, moving horizontally, but I had a strong suspicion that the surface, and the direction of my passing, defied one another, just as though they knew our relationship was out of whack, unnatural, much like a climber, five hundred meters high, hanging on by their fingertips.

Out of place.

Out on a limb.

Dislodging rocks as I went.

I moved like so:

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

22/04/2020

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

pick up

step step step

put down

rest

place place place

Does the word become the act?

23/04/2020

As I traversed the field, diligently planting, what I thought I knew annulled itself.

It stirred and revealed itself to me, as I shall now reveal it to you.

I realised that rhythm is one of the hardest things to learn, and one of the hardest things to gain. You see, I was never much of a dancer, or a musician, or a sportsman. I was never much of anything. And I’d be lying if I didn’t somewhat resent myself for that. They say you are born with rhythm. They say you are born with or without it. It is just one of those things, one of those many, many things, which we add to our long list of things we choose to live by; preordained, predestined shackles, heavy around our limbs. Me? No. No, I can’t dance. I never have. And I kind of always felt, if I did have it, I wouldn’t know where to place it. Take your good intentions elsewhere. Climatically: to gain rhythm is actually, to gain acceptance; to be rhythmic, is to know yourself.

I now suspect it, rhythm that is, as something extending out, and proliferating the world around us. Hidden behind shadows, doorways, laying under the earth. It appears like low lying mist, in the early morning air, the weight of gravity holding it down, making it a part of this world; it is so precious, so unique, it would depart us, should it get the chance. A flutter of golden butterflies. A splash of light. A breath as deep as the sea. You find rhythm in more ways than you know. In the words I use to write to you. And in the sentences I cobble together. I feel, sometimes, like I dance through letters and words. They carry us through the rhythm of the page. Much like music, building, growing, successively following itself, existing in and through time, the effects of which are at the mercy of experience and duration. I think I’ve found it. And I now point you towards the essence of music, dance, sport, and writing, as I now know it, and dare I say it, life, which I feel, deeply, in my heart: rhythm.

Oh honey, put on your dancing shoes.

Let’s hit the town.

Rhythm,

buried with me,

s

e

e

p

s

out of me,

into the ground.

Fuelling,

spinning the Earth.

24/04/2020

These pages, topple, like dominoes, threatening to crush me.

25/04/2020

I held the stone and it held my gaze. I moved it around in my palm, spinning it, overturning it, tracing and recording every inch of its surface; I noted its shape, dimension, colour and outline against my palm. By all appearances, it seemed ordinary. Ordinary like the rest. Ordinary like a stone. And much like the others, that had passed through my hand, it was smooth, greyish, dirty in places, and cold, cold to touch. But somehow, this one appeared different to the rest; it was out of the ordinary. Wherever the ordinary was, it had emerged from it.

It was heavier somehow. Heavier.

Or was it lighter? Lighter.

I glanced back, back over my shoulder, to see a line of stones following me to where I stood. Their length was far, their width, narrow. I felt like a celestial body, as constellations of orbs, of stones, circled and circled, orbiting around me. They grew, gargantuan, like snowballs, running down a great snowy hill. They lifted off and departed this world. It was then I became a stargazer, observing clusters of them, of stars, of stones, millions and millions of miles away; flickering, glinting, twinkling, their luminescence was sent back to Earth; they penetrated the atmosphere, and entered me. I was filled by their message and it was their message I did hear: they had come to lift me. And so, without hesitation, I went, beginning slow at first, but levitating nonetheless. I disobeyed gravity. Drifting far and drifting wide. Rolls reversed. Positions eroded. Now, it was I, orbiting the stones.

My stones are like grains of sand in the space of the landscape, I thought, as I soared and soared, high above. They were almost amorphous, transmuting themselves. If I’d looked away I would have lost sight of them. Perhaps, my talent as an artist is to walk across a moor, or place a stone on the ground. That would be a noble, simple life: I dreamt it, I believed it, I lived it, and it was done. Milestones are like chapters, spinning out from underneath me. Let’s be pragmatic about this. A precise thought, logical, crystalline like the material of the stone. A stone is a stone is a stone. Much like a waterfall is a waterfall is a waterfall. Is a stone just the idea of stone? There are parts of me, and parts of you, which become, parts of us. I gasp. I was mortally open, filled with groundlessness. I sensed my own finitude. A crack in reality had sent me into a spiral; the spiral begins, the spiral ends, the rest is a curve, much like a stone. I did not wish to depart this world without you. I struggled, kicked and cried, to turn the tide of my momentum. I wanted to return; to return to the field, and to you.

I was brought crashing, crashing like a meteor, back down to Earth.

I snapped back inside myself, and dropped the stone.

|

|

|

|

|

It landed, with a thud.

Indenting the earth.

26/04/2020

The eyes of the stone stared back at me. I could not plant it, I sensed that, deep in my gut. It was a ringleader and it would intoxicate the others. It seduced me. What’s more, I had an overwhelming urge to walk; to walk with it. And so I bent down, picked it up and placed the stone into my pocket. I gathered myself, and collected those little pieces of cosmic dust that had ricocheted around me. I calmed myself—deep, deep breaths—and began to walk. I took this route: straight on, out of the field, and into the lane; left, along the lane until I got to the T-junction; right, down into the valley, past the duck pond, and then up the hill, back out of the valley; right again, and onto the main road, I travelled along here for a while, passing the garden centre, passing the petrol station, passing the shop, what a lovely day for a walk; I shot a left, following the winding lane as it moved like a snake along a forest floor; I stumbled down into another valley, and immediately, headed straight back up, my legs burning from the height of it; next I went along the lane, until I met the greenhouses, and stopped, on the yellow line; right, past St John’s manor; left, down that grand boulevard of trees; I continued on, passing the occasional house, and farmland; after some time, I arrived at St Mary’s village, walked past the pub and the church, and pushed on; this is when I almost lost sight of it: why I was walking; devouring trees, devouring leaves, like air; I like the simplicity of walking, the simplicity of stones, I murmured to myself, as if trying to convince myself to continue walking; I did not deviate from my route, I persisted with it, along the same road, past the windmill, and then the road took a sharp right; I stared at the pavement, hypnotised, watching my feet, and my shoes, march on, as if they were possessed; a walk is just one more layer, a mark, laid upon the thousands of other layers of human and geographic history on the surface of the land; I considered my mark, and whether a mark was necessary, mark my words, you said to me; I took another right, so many, many rights, and eventually arrived at another yellow line, I waited, paused for the traffic, and travelled over the road and into the lane; I passed the pink house, and then I past Gran’s house, I poked my head around the gate, but she wasn’t in; her garden looked tranquil, sheltered and serene; whereas, on the lane, the vegetation looked barren, beaten and weathered by this stormy position; I felt that stone in my pocket, bouncing against my thigh, a tinge of sadness spread from my leg, and up into my heart; walking presupposes that at every step the world changes in some aspect and also that something changes in us; uncertain, my intent wavering, I became like that old tree, over there, creaking in the wind; at last, the road ebbed and flowed its way to a sweeping vista, overlooking the sea, and I emerged, high above the shore, on a cliff face; the air was fresh, and I filled my lungs; I followed the twisting, looping, bending road down to the beach at L’Etacq, and took the coastal path across the bay, along the sea wall; the curve carried me a great distance; the waves rolled in, and rolled out, as if pushing and pulling at my body; it was as though, I wandered, in and out of consciousness; I lost my balance, and was carried close to the edge of the wall; I peered at it, teetering on the brink, tempted to succumb to the vastness, to the sublime terror of height; I no longer sought to contain myself; my body demanded a metamorphosis, to transcend, to escape itself; my grip on the present and the past slipped away, time departed; my thoughts were flooded; the waves crashed, pounded, against the wall; I felt it, as if you were banging on my skull, cracking my head, like a stone in two; I stumbled on, and at times crawled, scraping my knees, cutting them, on the rough concrete; blood out of a stone; as I staggered to my feet, on my left, the white house floated by; the seagulls cawed, following me like scavengers, picking at the weak; the sun was bright, a bright, white light, and the swell shimmered and barrelled; exploding stars in its wake; I was nearing my end; I was nearing the slipway at Le Braye; words carried me the rest of the way. A thought enclosed in a stone.

27/04/2020

I reached it, not it…. don’t be foolish, not you, but something else; I jumped off the wall, onto the granite slipway, kicked off my shoes and removed my socks; I stepped off, my feet touched the sand, and it spread between my toes. The sound of the waves gently crashed as I walked further out onto the beach. A sense of relief pervaded and comforted me. I felt that I could swim for miles, out into the ocean: a desire for freedom, an impulsive to move, tugged at me as though it were a thread fastened to my chest. I released myself and sang a melody, it rose and fell, like light, dancing across the waves. A spirit filled him, pure as the purest water, sweet as dew, moving as music. As my song moved through the air, I scanned the horizon and noticed a figure, a lone figure, moving frantically along the shoreline. It was, alas, our runner, circling, searching for a line. A line in the sand. The line I had promised him. I was disheartened to see this, to see his madness creeping in; he should have begun, many pages and pages ago. I thought, perhaps, he may have lost sight of himself. It’s easy to do so, as you know. Especially in a place such as this: an abyss of sand; an abyss of you. I need not tell you what happens when you gaze at it.

I placed my hand into my pocket, grasped the stone, and lifted it out. When does a stone become a pebble? When does a mountain become a hill? It was slightly lighter than before. Our walk may have resolved it somewhat, but the stone trembled in fear, it was like an earthquake, the size of my palm. The trembling became an image, or rather, a fragment of it; it dug in, sunk its roots down, and burrowed into me; my soul separated itself from my skin, outraged, that an image had replaced it. The stone gave birth to the present. And it is the here and now where we find ourselves. I thought about throwing it at the rocks, catapulting it, to see it land, with a clap, and a thunder. Could I destroy this image; shattering it, into a thousand pieces? Does it have a fossil inside? A fossilised event, like a book, or a poem. I hesitated; I could not destroy a book, no more than I could destroy a person.

I wondered if the stone could grow into a tree of coral under the sea. A beautiful, kaleidoscopic world, a world where mirage becomes reality, where sight itself is not as distinct as it ought to be. I walked a little further, down to the water’s edge. The tension between me and the water grew, closer. I waited and as the wave broke, the sea came rushing up to greet me, like an old friend, long separated by time. What is the sea, the ocean, if not a giant basin of rock, an expansive network of shelves, surfaces, holding the water above it, in its hands or on its shoulders. I saw life made up of material, such as words, which I harness, alongside stone and water; permeating, spreading, or holding on, and standing firm. Breathing the air of the sea is like breathing the light. A clarity as fresh as the day. I was tempted to drop you in, to make you a part of the sea of stone. You’d be a drop, a drop in the ocean of stories. And maybe, that was that; these stones are like tales, whispers in the wind, departures, waiting to be nurtured and dropped into a melting pot of that which makes you. They are the things which direct, lead, and help you arrive. Like a blustery day, and a sail full of breeze.

The sun began to fall, the light, with it, and so the world did too, falling, falling around us. You were not an ordinary stone after all, but a curious one, from a family of living stones. I bent down, with the stone in my hand and drew a line, a line clear as crystal, unmistakeable, along the sand. The runner looked relieved, thanked me, from the bottom of his heart, and went on his way. I placed you back into my pocket, turned, and headed home. A living stone, I sang and sang. The stone and sea merged together and became me. A body of sea and stone.

28/04/2020

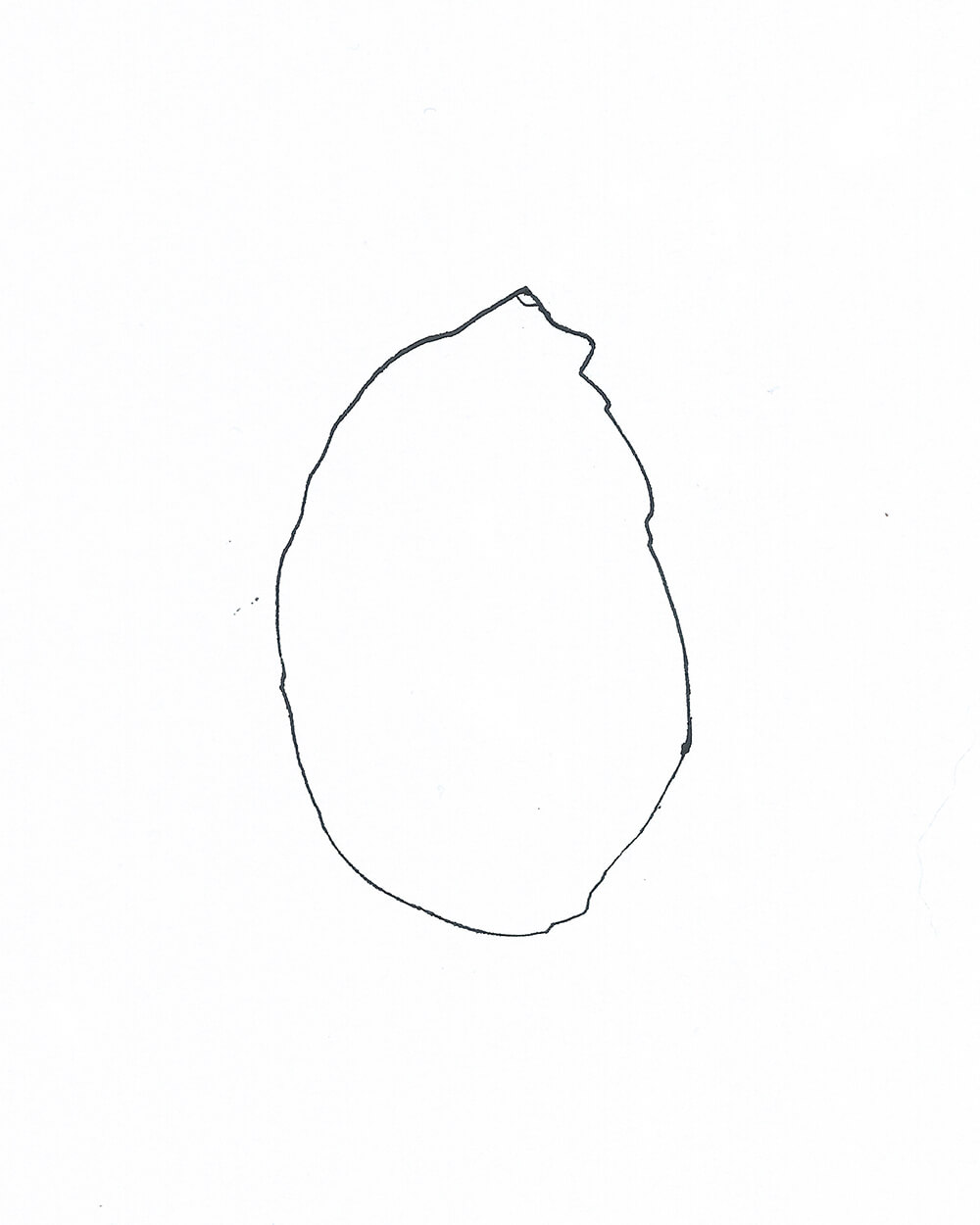

Outline of the stone, with the page, as my palm:

29/04/2020

What age does that feel? You asked me, some time ago.

It provoked me, in more ways than one.

30/04/2020

You have a different way of knowing yourself, you also said to me.

1/05/2020

As luck would have it, it is now, and only now, that you join me in the present. The present, whatever that may be.

It will come as no surprise to learn that I have been reaching for a while now, but whether it was towards, or away from you, remains to be seen. But, for some reason, it is now I feel we are on the same page. And I get the impression you’re growing impatient, as you’re endlessly pacing, like a bloodhound, restless to uncover the truth. To sniff it out, as it were. And after our walk, it pleases me to say we’ve bonded and grown familiar; and doesn’t it feel nice to lean closer, to lean on someone every now and then? Anyway, you don’t feel like a stranger anymore, that was my point, you’re more like an acquaintance. But an acquaintance I’m interested in understanding further. So that’s a good thing. That’s a good position to be in. I’ve noticed there two types of acquaintances: those you have polite conversation with at a bus stop, and those, who for some reason, you can simply slip into getting blind, raving drunk; speaking for hours and hours on end. I suspect, and hope, you may be the latter. At present, I am comfortable to share it with you, the truth of it, or, as far as I know it to be.

To help us on our way, may I point something out: you have asked me what and why, but you haven’t asked me where. And it is the where where the crux of this story lies; more so, it is not only where but the who we find there. I postulate that there’s something lurking in all stories, in all names, and in all people, and often, it’s telluric: it’s from the soil and it’s from the earth. What I mean by that is this: the where, from my experience, tends to be where most of you are found, nearby, deeply buried in the earth. And who are these you I speak of? Well, please don’t think me morbid, but it’s your family. Or perhaps, it’s just the case for my own family. Nevertheless, I believe it’s the who who dictates the where, and it’s the who which often ends up in the dirt of the where, and therefore, the who becomes inseparable from the where. And just because the who are in the dirt, doesn’t mean to say their value is worthless, far from it, in actual fact, their value can never, truly, be measured. These pieces anchor you to a place. To the where. Well, they do for me. You can choose to believe me or not, but that fact of the matter is, you never control it; it’s that place you first walked over, and in some respects, it walked over you. I’ve discovered, that over time, it can hinder, contain and control you; or it liberates, supports and ignites you. Its agency fluctuates. Its nature changes. Much like your passion for things. And whether it’s one or the other, it forms you, like a sculptor handling clay. The creation of life from clay. It’s known around the world as something to long for, or something you long to leave. It’s hard to make and easy to destroy. It is, of course: home.

It may also be prudent to point out: all the names mean nothing to you, and your name means nothing to them. And so, this journey into where and who, shall be, somewhat, a self-fulfilling exercise, an exercise for me to enjoy, and perhaps, you too, if you’re a person who can tolerate those utterly tedious stories, about other people’s families. I do often ask myself: is there anything more dull than feigning interest in Great Aunty Fanny? I think not; if there is, I haven’t found it yet. Needless to say, I will not be disappointed if you leave now. But if you choose to, if you will it so, we shall cast our minds back, back to the people and places that made me. Look at it this way: it might influence your form, or your shape; you may gain an aptitude for it, for recollections and for memory. After all, it’s in your nature to be nostalgic. To muse on the past, and to feel it in the present.

2/05/2020

If you flew, like a seagull, due south from Poole Harbour, at about hundred miles into that tempestuous sea, you would come across a scattering of islands, which can be seen, on a clear and sunny day, from each other. The place I call home is an island that sits in the Channel, the English Channel. They are positioned near the coast of France, but not too close to be France. Interestingly, they are the oldest possession of the British Crown. In the past, I have counted many acquaintances and friends, who have brimmed with joy, in mockery of us; and their comments usually go something along the lines of: Are you French? Is it just you and ten other people? Really? Do you really live on a rock, in the sea, with just a cow and a tree? As to why mainlanders find this idea hilariously funny still eludes me, to such a degree, I believe the island remains my secret. A secret from all those who are ignorant. In spite of this, the island which we are concerned with, is the largest, and has known many names throughout its time, given to it by its inhabitants and passers-by. Settle in. Sit around the campfire, and let’s begin.

It started with a rumour, amongst historians and writers, that the first name was once Cæsarea; believed to be given to the island by the Roman Empire, to help guide officials on voyages; however, in recent times, there seems to be no proof in such claims. During the 6th century, and coinciding with Christianity, it is thought the island had taken a new name; found during the Early Middle Ages, and located within the small chapels on the island, such as Fisherman’s Chapel; it was recorded as being either: Andium, Agna, Augia or Angia; some propose that Andium, roughly translated, could mean “large island”. Next, and perhaps pivotally, it was only after the invasion of the Vikings, or the Norsemen, between the 9th and 10th centuries, did a new name emerge; the one which would last to the present day. As with most things, this too is debated, but popular theories suggest that the Normans named the island Gers-ey. The reason as to why, again, remains unclear, but it is thought that the suffix “ey” is Norse for either “water” or “island”, and the meaning of “Gers” could perhaps be from the Frisian, which means “grass”, thus leading us to “Grassy Isle”. It is also popular belief, and my favourite interpretation, that the name hails from the Norwegian Viking who first seized and claimed the island, as Geirr is a personal name, resulting in Geirr’s ey or “Geirr’s Island”. Whatever the route, it is now, we arrive at Jersey, the island of Jersey.

You should note, Jersey has not always been an island, in fact, studies prove a great forest once grew between Jersey and Guernsey, stretching out from where the beach ends and the sea begins, across the water, to where the sea ends, and the beach begins. As sea levels rose, so too did the island’s tendency to dip its toes, then a leg, then a torso, and lastly, its whole body, into the tide of history: it has seen Palaeolithic hunter gatherers 250,000 years ago, the Neolithic period, the Gallo-Roman era, the Early Middle Ages, Vikings, Normans, the Hundred Years’ War, the Black Death, the War of the Roses, the English Civil War, the Battle of Jersey, World War I, World War II, a five-year occupation from German forces, and finally, its liberation on 9th May 1945. It is then an island drenched in history. The scars of which appear, intermittently, throughout its landscape. And as I stand here, in my field, surveying the land, I notice a block like structure emerging, disrupting my view, interrupting the sea of green foliage. It is a concrete, distressed, box shape. Something which I’ve always overlooked. My grandfather told me the other day, he use to play on it, when he was ten or eleven years old: on the German gun emplacement, he said. The sky above, is in the centre, or rather, this field is in the centre of the sky (in prime position of the flight path). It sent a chill, spreading down my spine. It dawned on me: it’s here history can be seen and felt.

3/05/2020

Image: Claude Cahun

4/05/2020

I could continue to select moments of history to regale you with, but it wouldn’t serve us well, as although we are indeed concerned with the distant, it’s the distant which grows near that captures us. And for me, no, for us, I should say, this exercise is not just about what happened when, but the nature of who we find there, and how they came to be there. Jersey has seen an array of notable inhabitants, and to name a few: King Charles II (1630-1685), the dethroned king, whilst in exile, sheltered on the island twice, during 1646 and 1649; Victor Hugo (1802-1885), the famed poet and novelist, also moved to Jersey whilst in exile from France in 1852; Claude Cahun (1894-1954), born Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob, was an artist, at the forefront of surrealism, who originated from Nantes, but later settled in Jersey; and lastly, Gerald Durrell (1925-1995), author and conservationist, settled here after life in Corfu, setting up the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust and zoo. These are names known widely on and off the island of Jersey. And why should you care? Well, that’s up to you. I sometimes find it insightful to learn which bodies have moved through this air. And those who have felt the island dwell inside of them. As it dwells inside of me. History is a place, a cave, which wraps around me.

I shall now attempt to follow the lineage of my family; for arguments sake, and for the sake of paper, I will only follow my paternal line, as best I can. It is believed the Mourant family, also spelt Morant and Moraunt, arrived on the island of Jersey as early as 1309. Research into the family has suggested that we are possibly descendants of the de Morant family of Normandy. As the story goes, the Viking, Rollo, landed in Normandy in 911, and signed a treaty with the then King of West Francia, Charles III; the king bestowed power and land onto Rollo, who became the first Duke of Normandy. The Duke’s fief (an estate of land), was known to be called either “Les Cours Morant” or “Morantsgaard”, which is thought to have originated from “morant” meaning “seamen”. As a matter of fact, it was not until Rollo’s son, William Longsword, previously Count of Rouen, seized the Cotentin Peninsula, during an expansion of lands in 933, did the Duchy come to possess the Channel Islands. The ancestors of Mourant, or the de Morant family, are recorded as being mainly members of the landed gentry or nobility in France. Historical references place the families presence as far back as Pierre Morant (1155), Olivier Morant (1195) and Raoul and Guillaume Morant (1195 and 1198), all residing in and around Normandy. The first mention of the family actually in Jersey, comes regrettably, in the form of punishment, as in the parish of St Saviour, in 1309, Ralph (Radulphus) Moraunt was punished for breaking a law governing bakers and taverners. Following this, there are the occasional records where the family name appears, such as in land transactions, legal documents and court appearances, all the way through the 15th century. The family seems to fragment during this time, with lines ending, and daughters being prominent rather than sons. Nevertheless, what is agreed upon as the strongest, longest and continuous line, begins with the birth of Drouet Mourant (1500-1580), or Morant (depending on which source you consult), who was baptised in St Saviour’s parish church, in 1500. Where the “u” came from in our name, still baffles and remains a mystery to me; as the name grew so did its meaning, as the “u” brings us to “Mourant”, meaning “dying” in French. However, it is from here, from birth rather than death, of Drouet Mourant, that a line emerges; or should I say, a tree, which we can follow; look, look up there, as I climb down from the highest most upper branches, descending from the zenith, making sure, carefully, to step lightly, as I move to the lower branches, and then onto the trunk, shimmying down, to the base of the tree, and onto the ground, down to me. You could say, he was a grand, old oak tree, and me, a sapling, slender and immature.

5/05/2020

What was our life like?

How kind of you to ask.

Our life in Jersey, over the past five hundred years, could quite accurately be summed up over the following lines: we were, and for all intents and purposes still are, quintessentially, farmers; our life was out on the fields and in the barns; it was about getting your hands dirty. And this was not unique to us, but to the island itself; Jersey had its cornerstone in a prosperous agricultural industry. The task, at first, was to grow enough food to survive, to feed a family of eight to ten children. But it soon grew into a prominent industry. The island had, and still has, rich fertile soil, and a favourable climate, which brings its crops to fruition a couple weeks prior to that of the mainland. It brought the island fame, and crucially, wealth. There are tales of farmers who produced their crops early, sold them to merchants down at the harbour (for a mind-boggling price), and then laughed, as they walked home, with a spring in their step, taking early retirement. Those were what you’d call the good old days. We were famous for four main things: cider, tomatoes, cows and Jersey Royal Potatoes. Two have died out and two remain.

We were, and again, still are a family, who pride ourselves at breeding prizewinning cattle and growing Jersey Royal Potatoes. The potatoes, started life as a bit of a fluke, and for a time, they were known as Jersey Flukes. As my father said to me once, it was Hugh de la Haye, who one day came across a potato growing which had sixteen eyes. The eyes of which we speak are actually sprouts; shoots from which the body of the plant grows up, out of the earth, towards the sun. This was extremely abnormal, and after Hugh showed this to his friends, they decided to cut it up, into pieces, with a stalk each and planted these into a cotil. A cotil is a Jersey term, for an early, sloping field, which is very small and difficult to manoeuvre around. They are south facing and experience maximum warmth and sunlight. After a heavy and early spring, Hugh noticed how one plant produced unique, kidney shaped potatoes. He continued to cultivate these, over the years, until there was enough for an entire field, crop and harvest. They tasted delicious, and popularity quickly grew; thus, a tradition was born. It may come as no surprise to you, but, at last, I can tell you: I planted potatoes too. I did that! I took to the field and placed them, one by one, up the furrows. They are what grow out there, on the land. And, they are what grow inside of me.

Lastly, our place within the place, had been the parish of Grouville, St Saviour, and St Helier. These parishes are closely knit communities, sharing boundaries with each other. So, over time, we did not travel far. Far in Jersey is about two miles, and that’s about the distance, if not less, that the majority of our family moved. You have to reorientate your sense of what is close and far here, both physically and metaphysically. The year was filled with tradition and hard, gratifying work. The children would walk to school, and walk back; the neighbours would know you, and your father, and your father’s father. You’d grow apples for cider, make black butter in the winter, make Jersey Wonders in the spring (as the tide went out), plant the fields, tend to the cows, harvest the crop, even the schools would close during the height of the season so the children could farm too. That was their life for generations, and of course, it was back-breaking and strenuous, and perhaps I’ve romanticised it, but it appears to be a good life. As much as there is unhappiness anywhere, I get the sense it was a better place than many.

6/05/2020

7/05/2020

My search has unearthed talent, notoriety and sadness amongst the family line. For a pastoral idyll, regrettably, is exactly that: an idyll; it is not realistic, or achievable. It lives as an idyllic image, in my mind, rising and setting, like the sun. The sum of it reads as a mixed bag; as with most families, there is lightness and darkness. For us, there was rampant alcoholism within our ranks; an infliction helped along by strong home brew cider. And in the 17th century, Jean Mourant, became known for witchcraft, and as a consequence, was hanged. However, happier revelations include: Rev Philip Mo(u)rant (1700-1770), a celebrated antiquarian and researcher into the Norman conquest; Sir John Everett Millais (1829-1896), the Pre-Raphaelite painter of the 19th century, who was a child prodigy, gaining entrance into the Royal Academy Schools age 11 (at the time of writing, his palettes are on show in the vaults); and, last but certainly not least, Dr Arthur Ernest Mourant (1904-1994), who was a highly skilled individual, recognised as a geologist, haematologist, chemist and geneticist. It would now be apt to reveal to you Dr Mourant’s book, Blood and Stones, which is the text I currently consult about who and what we are. Besides the fabulous title, which I envy, I shall forever be indebted to him for discovering our ancestry. His death, was in 1994, which coincidentally, was the year of my birth. He was also a lover of photography. Although, I do not for one moment attempt to draw any similarity between the little I know, and understand, to the seemingly stratospheric intelligence and wisdom of this man. But I’d be crestfallen if I did not declare the kinship I feel towards him; and despite the fact our relationship is one through a tenuous link, it is a link nonetheless.

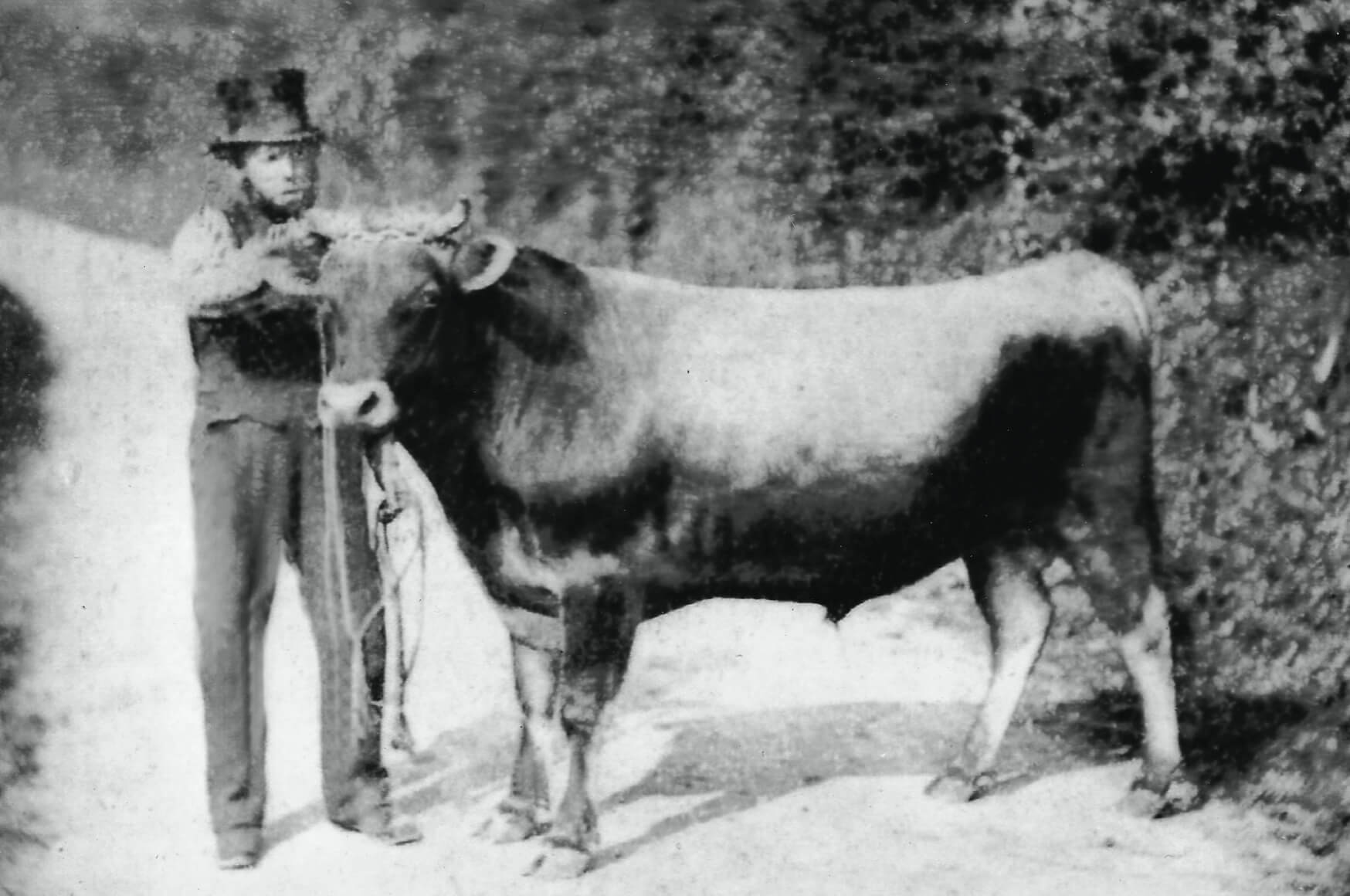

Right, with the help of Dr Mourant, let me attempt to break this down: the man in the picture I showed you yesterday, to the left of the horse, is my great-grandfather, Edgar Reynolds Mourant (1909-1971), the man to the right, holding the plough, is my great-great-grandfather, Philip Chevalier Mourant (1875-1967), and Philip’s father, was my great-great-great-grandfather, Philip Joshue Mourant (1831-1892). With me so far? Great. Next, Philip Joshue Mourant, was the brother of Charles Mourant (1840-1920), and Charles’s son, was Ernest Mourant (1872-1958), whose son was our Dr Arthur Ernest Mourant (1904-1994). It’s a delirious and tenuous link, like I said, but we both share a love of blood and stones, so I shall carry on. When reading Dr Mourant’s autobiography (the aforementioned title), I came across an interesting piece of history which was unknown to me. He writes: I cannot trace my own ancestry in the male line beyond my great-great-great-grandfather, Jean Mourant, whose son Philip in 1818 bought the farm at Haut du Mont au Prêtre in the parish of St Helier, which has remained the home of the senior branch of the family. He goes on to mention that his grandfather, Charles Mourant, lived there too when he was a boy. This was enlightening, because, owing to the fact Dr Mourant’s grandfather grew up in that house, it would also make sense, that Charles’s brother, Philip Joshue Mourant (my great-great-great-grandfather), did too. Again, this may be uninteresting to you, dear Reader, but it was on the 10th August 1973, when my own grandfather, Stewart Mourant (1940), purchased Haut du Mont, from a close descendant, Philip George Mourant (1919-1988). After my grandfather lived there, some years later, he moved next door, and my own father, Nick Mourant (1964), came to live there, and brought up four children: Georgina Mourant (1989), Stephanie Mourant (1990), Bryony Mourant (1992), and then myself; which leads me, and you, to this wooden desk where I now sit, writing these words, in that very same house. I gaze up and stare at the surface of the granite walls, weathered by hands over the years. If these walls could speak, I thought. How bizarre it feels to write history when I’m not only touching it, but sitting inside it. Words welcome us; we inhabit their walls.

8/05/2020

The reason why I brought you here, was not only to visit my house, or to meet Dr Mourant, but to speak of our ancestors, Charles Mourant, and my great-great-great-grandfather, Philip Joshue Mourant. You see, about a year ago, I learnt of their tales and exploits. And at the time, it seemed like quite a grand and exciting story, something which I thought you’d be interested to hear. Indeed, that was the plan, until I learnt of how the story ended, for Philip at least, and then it became achingly sad and troublesome. It became a story I wasn’t sure of how to handle; how to spin or weave it. It felt wrong, but it also felt essential to this, to our story. And I had to judge what was best for you and for us; to weigh them both up. I decided, as I was sucked in by this story, enthralled by it, I should attempt to recall it, no matter how shameful it feels to be doing so. In terms of records, or factual basis, time has done away with most of the details, as time often does, and my family holds hardly any documents. And so, what I tell you is supported by what was passed down, by what was disclosed; and I’m certain, what was spoken, was affected, by what was unspoken. It started as a family rumour, and the more it was said, I guess, the more it was said to be true. Like liquid cooling, through the generations, to become crystal inside us.

I’ll stop beating around the bush: as I mentioned, they were brothers, and Charles was the younger. They grew up at Haut du Mont, as I did, became young men, and followed their own paths. Philip, being almost a decade older, was expectedly, the first to marry. He married Mary-Ann Le Gallais (1829), who bore three children: Philip (1859), who sadly died in infancy; Mary Ann (1860) and Emelie Rachel (1861). At this time, Dr Mourant speaks of Charles travelling: he headed out by sea, sailing far and wide, reaching as far as Barbados. Upon his return, he too married and continued to farm at Haut du Mont. It would seem, after a while, he decided to move to his own house at Croix ès Mottes, St Saviour, which is nearby to La Hougue Bie; shortly after, Charles had his first child, a son, Ernest Mourant (1872), and it was there, at Croix ès Mottes, where he spent the remainder of his life. Unfortunately, in the 1860s, Philip’s wife Mary-Ann, died, as to why, I could not find out. It was then, in the late 1860s Philip remarried, to Mary-Ann’s sister, Louisa Le Gallais (1839), who bore five children: Louisa Alice (1870), Clara Jane (1873), Philip Chevalier (1875), Harriet Vivian (1880) and Eva Ann (1882). A census of 1891, puts Philip’s family all in residence at La Commune Farm, St Saviour.

Professionally speaking, their life was quite successful. Both brothers became notable farmers on the island. I believe they grew crops, but their mainstay was cattle; they bred, prizewinning and lucrative, Jersey cows. For those in the dark, the Jersey cow is a unique, purebred to Jersey, becoming recognised as such around 1700. They have a golden coat and a friendly, docile temperament. They produce sought after rich and creamy milk. There even exists the Jersey Herd Book, founded by the Royal Jersey Agricultural & Horticultural Society, as a record of the Jersey cow’s ancestry (its pedigree), much like a family tree, dating back to 1866. In fact, so great was the interest in breeding and showing cows, that still to this day, Jersey holds a biannual show, of which I remember my sister, Georgina Mourant, competing and winning a rosette when we were kids. And when I recall our childhood, it is one of cows in the shed and in the fields. Just before the turn of the millennium, we had around five hundred head of cattle. And once, to mark the occasion of Prince Charles and Lady Diana’s wedding, my grandfather’s cow, named Regal Absorbine Dream, was selected and gifted from Jersey to the Royal Family.

9/05/2020

10/05/2020

Anyway, I digress. Let’s return to Charles and Philip. Their reputation had grown over the years, but, more so Charles, who became perhaps the most successful of all island breeders; they exported cattle to the mainland and further afield, such as America. What quickly followed, I trust, was a sizeable fortune for the time. In one particular case, in 1919, a bull named Sybil’s Gamboge (bred by Charles Mourant), sold in New York for a world record of $65,000, roughly a million dollars in today’s money. This sale caused such a frenzy that the bull, later, was transported to New York City, and paraded down Wall Street. This was the first case, I imagine, of a bull actually being on Wall Street. Furthermore, the bull’s daughter, Bagot’s Gamboge Crocus, sold for $10,100, and fifteen other daughters brought around $3,000 each on average. By 1921, the bull’s offspring had culminated total sales of $500,000. It was like selling racehorses. And although, it must be said, Charles Mourant experienced this grand sale in the final year of his life, I believe both brothers had good fortune in their exploits for most of their life. It was said they were able to purchase farms, early land and build multiple barns for their herds of cattle.

It is with a heavy heart, that I inform you, this good fortune came crumbling down in 1892. From here seeps the darkness; the darkness of this tale, like a pool of blood, soaking into the page. In the early morning, on the 29th of October, a servant, called Louis Allouis, rose to attend, as with each day, to the cattle in the stable; as he walked in, he found his master, Philip Joshue Mourant, hanging from the rafters by his neck. Allouis immediately called for help and attempted to lift Philip’s weight. Only when joined by the other servant, Jean Baptise Martin, could they lift him, remove the rope, and place Philip on the floor, outside the stable. Life was extinct, but the body was still warm. They rushed off to get assistance. But it was in vain, as he, most definitely, had departed this world.

Mystery still surrounds the exact circumstances which lead to Philip’s actions that morning. He did not leave a note. Witnesses in the inquest said they had seen Philip become elusive, disheartened and distant over the past few weeks. His brother, Charles, also commented saying he had noticed his brother was low-spirited, upset by the loss of his cattle and a poor year on the farm; however, Charles felt although downcast, Philip never insinuated anything which would lead him to do such a thing. He was reticent, and plagued with worries, which rattled around his head; people close to him, such as the stablehands, had seen him speaking to himself, in the weeks prior. Muttering. Muttering. Muttering. I would say then, he tried his best to conceal his desperation from others. Bottling it all up. And as our family stories now suggest, it was not just a poor year on the farm, but a bank collapse, which had absorbed his life savings, and left not a penny to his name. Others propose, as I had mentioned before, that alcoholism had a part to play. Whatever the story, it seems dear Philip was suffering from an intense depression. A great sadness which must have welled up inside of him, like an incoming tide, raising a boat, and taking him out to sea. I think he was concerned, most of all, about not just the money, but the loss of his reputation: about what the family would think, and how they would feel. You must not forget, this would have caused quite a stir at the time; there was utter disgrace in bankruptcy. A stir which he felt, would have been too much to bear. It weighs down on me, like large, ever filling anchors, to picture him there, on that fateful morning, aching, as the image of himself, that boulder of all that you are, resting on your shoulders, was shattered, crushed, ground away, into a pile of sand. Was he on his hands and knees, as his image, severed from him, became sand, and slipped through his fingers? Perhaps it’s the sheer weight of it: the weight of history. It pulverises.

11/05/2020

Suffering, like a stone…

(around my neck,

deep inside me)

12/05/2020

As dust or ash, floating in the wind.

To learn of Philip Joshue Mourant’s demise, was to learn of something fundamentally absent. I use the word demise, as in a sense, it was. And I can see how that makes him somewhat mythologised. As if he was a character: characters don’t just live and die, they are born out of suffering, they ascend to vast heights, and they fall, like Icarus, into an ocean of demise. Often we’re told as readers, the reason for a fall is excessive hubris. To become the fallen you must believe, that your means are over and above yourself. And it’s the universe’s way of levelling the playing field. As life is a game. A terribly sordid game, which you can quickly grow tired of. It reminds me of what is veiled, behind writing and photographs: suffering. We are bound to suffer through them, to open ourselves up to the unfathomable depths of them, as although they teach us, and introduce us, they often take more than they give; we’re reminded of all that we don’t have. And that’s mourning too: the expanding absence of the heart, the knowing that chance, choice and destiny no longer remains. It is set in stone. No more throw of the dice. And that’s when tragedy occurs: when the one who grows absent, abandons chance, too early.

In the wake of discovering Philip’s death, my grandfather and Stephen Mourant (1954)—another relative who is a keen researcher, and architect of our extensive family tree, and again, must also be thanked for his assistance—together, set about locating his remains. They drew a blank when attempting to locate his burial at cemeteries in both St Helier and St Saviour. It seems, as a result of his suicide (his blasphemy), the church did not allow him to be buried as tradition would have it, in the family plot, or recognised, for that matter, on the land of the church. Therefore, he went into town, which is now by the police station, and was laid to rest in what is known as Green Street Cemetery, or Stranger’s Cemetery. It was a place for those, as the name suggests, who were lost in some way; wanderers without a home. And after some back and forth correspondence, and digging in the archive, he proved quite hard to track down, but, eventually, they found him, and they learnt his burial was recorded, on the 31st August 1892, on the east side, in a grave with no markings of any kind, just a number: plot 345.

It was in early October, when I set off, with my father and grandfather, to visit Stranger’s Cemetery. We had the map from the archives, the plot circled, and we were going to visit the man who, to all of us, was a great-grandfather. There was an air of unreality. The day was clear, with gentle, soft sunlight, dappling on the surface of things, highlighting overgrown grass, trees and ivy, which felt as if they encroached further, as we stood there, threatening, or inviting us to become them. And after some confusion, misdirection, and the occasional frantic turning of our map, we eventually found plot 345. As promised, there was no headstone, just a little block of granite, with the number engraved, worn by time. The ground was patchy, with clumps of grass, but mainly, it was a blanket of dirt. There were the occasional specks of yellow and orange, colour from the fallen leaves of autumn. All three of us stood there silently; musing on what it is to become just another number, in a field of unknown people. It stayed with me, as things occasionally do. And with that, it felt like another tale was laid to rest, in the ground and on the page. And perhaps, as memory attracts memory, it grows anew.

13/05/2020

14/05/2020

A letter from my grandmother, Rosemary Mourant (1940), pertinently titled, Life on the Farm:

I am Rosemary Querée, am one of six children, we live on a farm down Rozel called Hillside, my parents are Wilford and my mother Lilian. I was able to leave school at the end of the spring term 1954, as my 15th birthday fell during the school holidays. My mother was not keen for me to stay on the farm, preferring I follow my sister Doreen who was a medical sectary at the General Hospital, so for a week or so I had to learn 10 medical words and their meanings, as I had no intention of going in an office I just didn’t learn them!!!!! So my life on the farm began. The days were long, but as long as I was outside I was happy. Dad would call us about 6:30am, had a cup of tea then out to the cow shed to milk the cows by hand, after that clean the stables, then take the cows out to grass, they were all pegged individually, someone had to come and move them onto new grass at least twice a day.

When it was a planting day, Dad liked to be in the field by 8:30. Dad sowed the fertilizer by hand, so Muriel and I had to keep him going by running on the ploughed field with a galvanised bucket so he never stopped. It was one of the hardest jobs we did. So my dad would make the furrow with the horse (Bella) and plough and the three of us would plant the potatoes in the furrow making sure we were finished by the time Dad came round again, we were always pleased to see Mum around 10:30 bringing us a sandwich and hot coffee made with boiled milk, it was really good. If after we finished planting it was still daylight we would pick up all the empty boxes carrying 8 at a time to the end of the field. After the days planting we had to milk the cows feed them etc then come in for our tea, then wash and bed.

We didn’t work like that two days in a row, as Dad had only one tractor, he would plough the next field while we would look after the cows and load the trailer with the seed potatoes ready for the next day and take care of the cows, few pigs and about 30 hens. Muriel and I were known as the ‘girls’ and for several years when we had finished planting on our farm, we were in great demand to help others, the trouble was when they knew we were there they would have a really busy day, we both worked very hard. We must have been rather naive, we never thought of being paid, so you can imagine when our grandfather came home and gave us each a £5 note! We thought we were millionaires. We had done two days planting for him.

As I have said before I just loved being in the fields with my dad and Muriel and Graham, although going to the other farms was really hard work. So I know how hard it is to plant by hand, I wish you all the very best, just for giving it a go. Will be there with a hot drink and some goodies to keep you going. I have asked M and G but we don’t have any photos planting, but we do have 2 digging.

Love Gran x x

Emailed: 5:07pm, 15th January, 2020

15/04/2020

16/05/2020

In the spirit of wholeness, I thought I’d share that my mother, Andrea Mourant (1959), also has farmers on both her maternal and paternal lines, as do my grandparents Pam Labey (1933) and Roy Labey (1932-1986). So, rest assured, whichever road we were to take, across this landscape of who and where, would have led us to the earth. I have learnt we are inextricably linked, bonded, to this island in the sea, and to its soil. Tomorrow, I shall leave you with a photograph of my great-grandfather, Stanley Alexander (1905-1985), furrowing and planting potatoes down at L’Etacq, where we walked, if you cast your mind back, with that heavy, curious, little stone, in my pocket. I have discovered the mixture we all carry, in one way or another, inside us: blood, stones and earth. Endlessly.

17/05/2020

18/05/2020

We have now learnt about the past and the past has learnt about us. And how does that make you feel? Do you have a renewed sense of purpose? Do you feel assured within yourself, by a grounding; or, like me, are you adrift? In-between: here, there, somewhere. Who knows, and at this point, who really cares? May I share an observation about writing historically with you: it felt dry; really, really dry. It was as if those words were heavy, cumbersome and featureless; and I could not mould or sculpt them as I usually would. They lacked plasticity. I was honestly struggling to pull those threads out, to join and weave them. It was extremely frustrating and I’m unsatisfied by the mess I have made. I was sure of it, you know, that they were betrothed, destined to dance: meant to be; to be here, with us. And perhaps, it will come across as a failure on my part. When we both stand back and look at you from a distance; from a place of clarity and objectivity. Remember: you must never force things into place.

They just didn’t want to fluctuate, or move, that’s what I’d tell or beg the officer; they exuded a certain inertness, an inhospitable nature engulfing the page. I had to be done with them. Like cracked clay along a river bed; or stretches of sand in a desert; or this earth across my field; or this dryness in my eyes: thirsty, parched, gasping for a drink. I’m wearing contact lenses today, as my glasses snapped last night. I’m not fond of them, contact lenses that is. They make me squint. They make my eyeballs squirm. It’s an addition to the daily torment I must endure. They make me see through dryness, and in doing so, they distort my sense of things. I catch myself looking at opaque forms, as globules of glare, float through my line of sight—the lenses, catch on my skin. It’s like smearing Vaseline across glass. I’m hallucinating. There are animals with dry eyes, like the snake, and those, like us—yes, yes indeed we are animal—who have, what you’d call moist, wet eyes. I wonder, as the snake, often deceives us, is it not then the nature of dryness to fool and trick us. To encircle us. To constrict us. Is it the nature of water to be truth: to sweep us away down the river. Is dryness a form of blindness? Do my eyes weep to seek the truth. They weep, as they learn the truth, I know that to be true. And hasn’t the eye often betrayed truth, or, rather, escaped it. Like the fugitive, spinning a web of lies. What then is the fate of words, or writing, which feels lifeless and dry, like my eyes. To write, is to give it form: a body of truth. It’s the texture of truth which makes us believe it.

A storm brews, there is thunder and lighting in the distance.

One-Mississippi.

Two-Mississippi.

Three-Mississippi.

A clap of thunder.

You’re not far.

I think the closer I get to things, things which matter, then the harder it is to form. To form the words through which we speak. The rains come, and I shall quench my thirst. The truth of the soil. Weeping eyes, beckoning.

19/05/2020

It will come, writes Rilke.

As to when, well, that’s another matter entirely.

20/05/2020

I sheltered at the base of a tree. The tree I mentioned before, that grand, old oak tree; I stood there hugging its trunk. It helped me endure the storm. And you should know, if you choose a tree large enough, one with a large enough wingspan, not a drop of rain will touch you. That’s a funny idea, isn’t it? The idea of a tree flapping its branches with such a force, it were to uproot, and transport itself, like its seeds, catching the breeze, and floating in the wind. A reversal of roles. But the wind does not stop for my thoughts. I’m not sure what the terminology would be for that: for the area covered by the branches and leaves of a tree; how it occupies the sky; and how it fills the air. There must be a cumulative name for its radius, circumference, perimeter; for its volume. More so, imagine a flock of them, a colony, a congregation, a murder, or whichever name it may take, flying high above us, casting shadows the size of a field. We’ll have to find another word for that too. We seem to be in the business of naming at the moment; the storm blew itself out, and with it, our grasp on the formation of what-d’you-call-it, oh, what’s-its-name, oh yes: things. Time is scattered, the past and the future, the future past and present. Blowing.

I sat on my haunches, with my back leaning against the bark, panting, slowly catching my breath. I collected myself and gazed out of the shadows. The clouds appeared to dissipate, moving on, and the sun emerged, triumphant; streaming light, glistening across beads of water, on the field, on the grass, and on the plants, like diamonds, falling and spreading along the floor, from a hole in your pocket. In front of me a jade sea is running wild. Waves crashed, virid spray. I had not yet told you: you have emerged. You broke through the surface a few weeks ago. And how I welcomed you to us. But it was then, after the rain we just had, that you looked vibrant and full of youth; luscious and green. Your leaves had grown and the sunlight, bouncing off the earth, radiated out through you; it was as if I stared into an X-ray, observing your arteries and veins. And the earth looked relieved too; the soil, which was almost dust, had returned, a dark, fertile brown. I thought: what makes the colour of soil? Even the ravines on its surface, those dry, barren cliffs, transmuted into gently rolling hills. Everything seemed to expand, in relief, in the pleasure of water and the waking of sunlight. An aroma of petrichor filled the air; it was intoxicating. A scent so sweet, it flowered inside my nostrils, as if Demeter herself, breathed it.